This autohistoria, or “a personal essay that theorizes,” is a special piece to me.[1] It is spiritual, poetic, political, and dialogic. This essay thus delves deeper into the mourning, the fear, the tears, the pain, the loneliness, the strength of a Vietnamese queer immigrant in a state of Nepantla in order to relate with other queers of color in the dark (i.e., in suicidal process). “Living in Nepantla, the overlapping space between different perceptions and belief systems, you are aware of the changeability of racial, gender, sexual, and other categories rendering the conventional labelling obsolete.”[2] In this space, I attempt to use the concept of Nepantla to describe and understand stages of pre- and post-suicide attempt that I experienced. Then, I will conclude with a call for policy change to ask for attention to those who live in the life-death margins and in between and among worlds as mine.

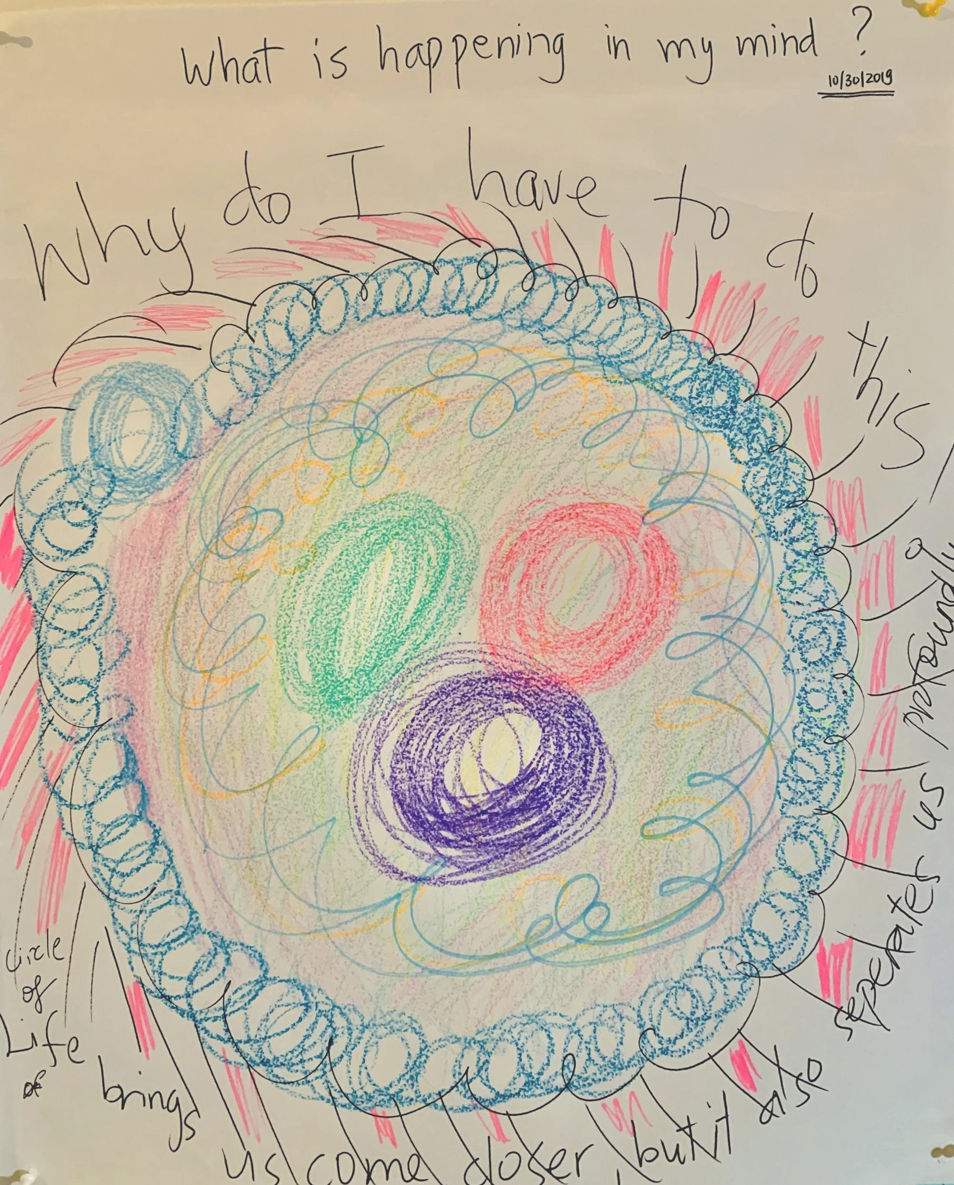

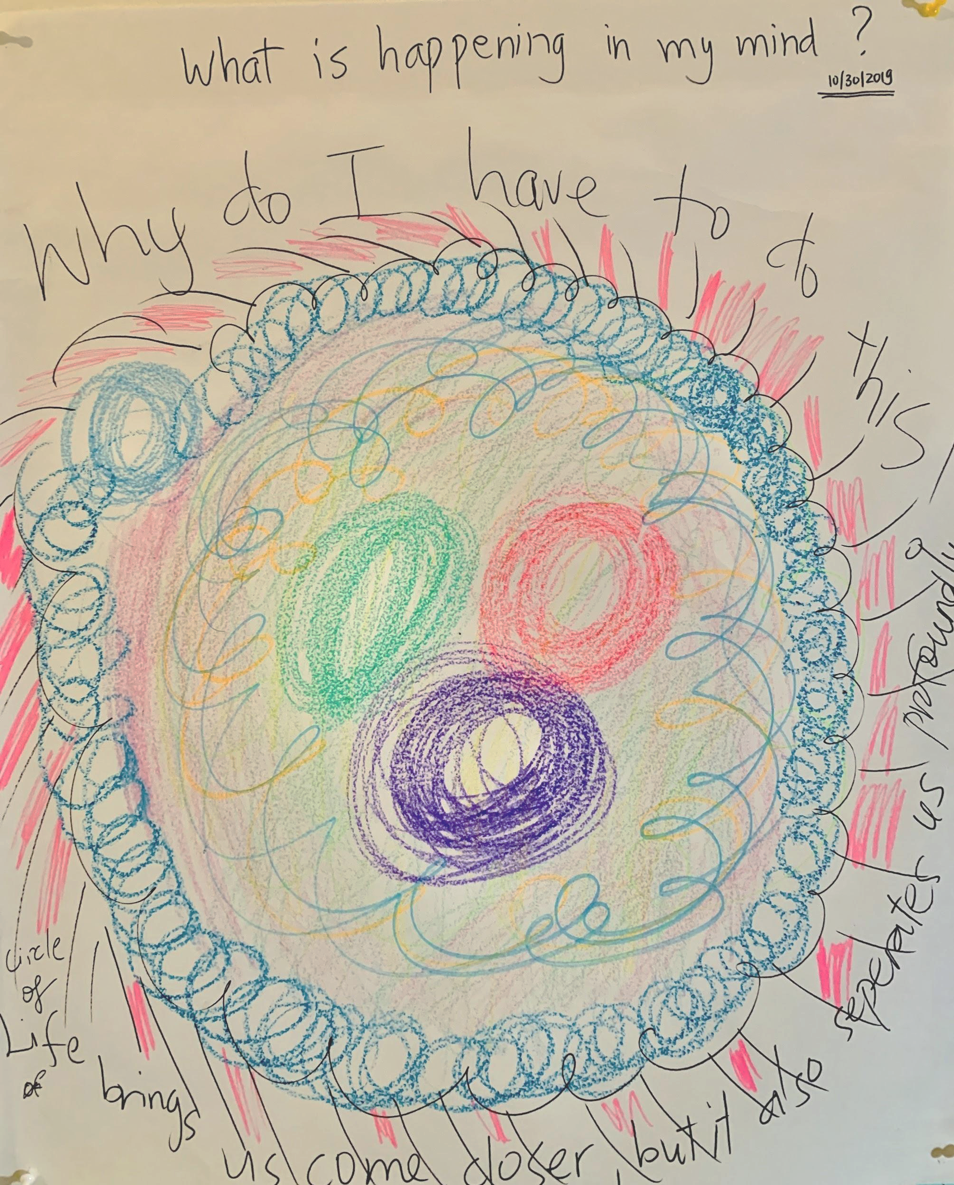

I am standing in my house. Drawing. I close my eyes and draw whatever comes to my mind. I am not an artist, but I draw shit out of my head on this blank page. I draw from extreme sweat. I draw from anxiety, depression, and liminality of this house, this room, this restrictive and systematic structure that is policing, caging, oppressing my body, my tongue, my soul. I draw to get rid of responsibilities, rules, doctrines, and power. I draw so I can fly with a spirit out of this physical space. I draw toward freedom and liberation for my soul.

The colors intertwine and weave together. The circle is fully formed. The chaos is formed in a structural way. What does each small circle mean? I do not even know because in each circle lies a hidden meaning that I am trying to figure out. However, a big circle outside represents life/death boundaries. The pink rays represent rays of fire that are burning me up. My skin is not physically burned yet, but my mind is. The heat is up, which will burn anything that stands in the way. I am not afraid of anything. I am committed. A circle of life brings us closer together, but it also separates us profoundly and permanently.

Fig. 1: I call it “circle of life.” I started to put color on the blank page and drew whatever came to my mind. E-v-e-r-y-t-h-i-n-g.

Triggers

It is a quiet evening. I am walking around Woodruff Park in downtown Atlanta; I cannot hear any voices. It is strange and unusual. This park is always crowded and busy with groups of tourists, students, and people. Tonight, this space is as quiet as a mouse. However, I do not see “mouse”; I see “rats” instead. I see big rats moving around downtown. They are probably looking for leftovers in trash cans near the park; or perhaps they are looking for a shelter to survive the night. Rats are brave warriors; they show up in public as if they want to say, “Look, I am here, I am harmless, look at me.” Sadly, I am not as brave as rats. I am not brave enough to confront myself tonight. I am not brave enough to confront the pressure of turning in manuscripts for journals by deadlines. I am exhausted after a long night staying with my mom; she is still in pain and in extreme shock as she was in an accident last night. She did not know what to do except to call me while I was still working a late shift downtown. I am devastated as I could not secure a teaching job due to my fight against the system; I fought fiercely for immigrant students against a capitalist school system. I neither want to think about how to pay my student loan with increasing interest nor to think about an argument with my brother as he rejected our brotherhood since he learned I am queer. As an immigrant, I am not allowed to be queer; I am not allowed to be broke; I am not allowed to take care of my sexual needs or to accept my gender identities. This is not a priority for our family now. I am walking to nowhere; my footsteps are heavy and lost. They walked me around the circle of the park, then came back to where I first started. I get lost in my own walk.

I am meditating while I am walking.[3] I am listening to the quietness of the park, which is comforting me, my soul, my worries, my queerness, my oppression. As a Vietnamese queer immigrant, graduate student, and Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) teacher of color, I experience the quadruple of oppression in a racialized hierarchy in the United States due to my accent, my Asian fat look, my immigrant status, and my sexual minority.[4] I attempted to turn my bilingual tongue, my in-between-ness identities, my minoritized gender identities, into strong shields to protect and uplift me and other marginalized populations from being sexually, mentally, racially, linguistically, and physically abused and discriminated from heteronormativity and homonormativity.[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10] I tried to overcome fears of judgement and isolation from the public. I act to be a happy, energetic, positive person that one wants to hang around and share with. I train myself to hide my real emotions. I have assimilated to Western cultures where I leave emotions at home and bring a different identity to work, to schools, to public. I thought I had successfully created an identity that performs well in a heteronormative society.[11] But tonight I refuse to perform my roles.

I a m e x h a u s t e d.

I drag my body out of the park. It is enough for a night’s walk. I drag my body to an elevator to take me to the 25th floor so that I can finish the last day of class. A classmate is presenting her work about a suicidal topic. I am attentively listening to her. “Suicide is interesting,” I thought. I was triggered by a topic, by a word, suicide. Since then, it is the only word that reiterates in my mind. My exhausted body cannot resist the attraction of this word. My stomach hurts. My mind is running chaotically. The quietness of the park has been replaced by a crowded, noisy space. I do not know what that is. “Is it a spiritual call?” I am wondering. It sounds like a lot of people are talking to me, pushing me toward an edge. I am walking out of the class while my classmate is still presenting. I drag my body close to the glass, looking out of the window from the 25th floor. The sky is beautiful, even though the clouds have turned dark. “What if” is a rhetorical question that comes out of my mind, back and forth, loudly and noisily.

My stomach hurts. Again. Real bad.

I kneel for a moment, then I stand up.

I come back to class. It is my turn to present.

I scanned each face in the room and said:

I want to tell you one thing before I start my presentation. I just want to go home safely tonight. I was triggered by the word suicide. I hate to be seen like this in front of everyone, but I wanted to tell you that I am fucking scared right now, I am scared that I won’t go home safely. I want to go home safe. Someone in my head told me that I needed to follow them. I stood at the window when we had a break, the question “what if” came to my mind. Voices told me so, but I resisted. My stomach hurts real bad. My fingers, my hands are still shaking if you notice. I hate to be seen like this. I don’t want to die. I guess what triggered me to have this suicidal thought was the pressure of recent accidents that happened to me and a self-hatred of being linguistically, sexually and racially abused in this fucking Western society. I am so sorry, everyone. I do not want to use this space as a counselling session. My counselling sessions with a white dude suck. But I feel safe in this space. I feel I needed to speak up, to expose myself, to tell you that I am now brave enough to continue this life.

Class is silent.

A friend brought me a crystal stone to keep me calm.

I am holding on to it as a faith as if it

will protect me from emotional abuse and labors.

I am standing there. Crying.

Crying heals my soul and waters its dryness for recovery.

A friend then exposes they are a survivor of sexual child abuse.

A friend then exposes they are lost at the intersectionality of

Queer, Black, Woman of Color.

A friend then exposes they are now brave enough to speak up for themselves

Because-someone-out-there-is-brave-enough-to-speak-up-about-themselves.

Because-i-am-brave-enough-to-speak-up-about-myself-in-front-of-them.

Session ends.

We hugged. We cried together.

Friends left pieces of paper on my desk, stating “Call me if you need to.”

Spirituality

I stand here.

watching him

alone,

calling suicide hotline,

“Hold on, I will transfer you to someone else.”

No questions.

No responses.

Beeeeeeepppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppp.

The length sounds like a sound in a hospital

as someone just passed away.

I stand here.

watching him

alone

jerking off

for escaping loneliness.

for an easy sleep.

I stand here,

watching myself

a l o n e

in the dark.

Back to Nepantla space

You are confused, aren’t you? I am drawing, standing, writing in an in-between space called “Nepantla.” According to Gloria Anzaldúa, a Chicana feminist, thinker, writer, and philosopher, Nepantla “indicates space/times of chaos, anxiety, pain, and loss of control … underscoring and expanding the ontological (spiritual, psychic) dimension.”[12] I fell into the chaos of time and space. I lost control of my physical and mental body. I was almost gone for being pushed to an edge of life and death when I thought no one cared; when I thought I was invisible; when I thought my life was full of pressure; when I thought I did not have any light of hope to hold on to, due to multiple oppressions that are put on me, as a lonely queer Vietnamese immigrant living, studying, and teaching in the United States, a Western, binary, and heteropatriarchal society. “Living in Nepantla, the overlapping space between different perceptions and belief systems, you are aware of the changeability of racial, gender, sexual, and other categories rendering the conventional labelling obsolete.”[13] Living in Nepantla helps me “see through,” develop “perspectives from the crack” in my own queer self in order to understand multiple stages of thoughts— mentally, physically and spiritually—to connect with other lonely queer people, and other queer people of color.[14],[15]

As Anzaldúa states, “In this liminal transitional space, suspended between shifts, you’re two people, split between before and after.”[16] I was, then, split between “multiple realities:”[17] transforming from a lost soul who draws a circle of life, a lost soul who walks alone in a park, a lost soul who stares at the window from the 25th floor, to a brave soul who talks about suicidal thoughts in public, a spiritual soul who witnesses my own identity struggling in the dark, and a critical soul who is writing this piece to connect with others. Not only do I own a physical soul, but I also possess a spiritual soul to see between the cracks of life. I used to write to connect and talk with Gloria Anzaldúa’s spirit when she was about to be free from this liminal space.[18] Now, I continue to write to connect with you, those who want to know another aspect of a person who has suicidal thoughts, those who are curious how the suicide attempt feels like.

Further, I crashed into different situations in which I faced loneliness and pressure to perform in this heteronormative and homophobic society. I was killed gradually by biases and stereotypes rooted in classism, sexism, and racism toward a Vietnamese queer immigrant struggling to navigate the system. Fortunately, my exposure to vulnerabilities allows me to connect with other vulnerable souls whose real emotions, feelings, and authenticity are hidden and unspoken; it’s like the three small circles in my picture: unknown, unnamed, undepictable. We are all buried alive in our own secrets, our pressures, our none-of-your-business thoughts. We gradually die—silently and unnoticeably. We refuse other people to come into our Nepantla space. We are afraid people will see our splits, our in-between-ness, our lost soul. However, my story, my exposure, my openness, and my tears are an invitation to connect with other individual vulnerabilities to witness my pain, my growth, my courageousness, and my minoritized identities. “Staying despierta becomes a survival tool,” states Anzaldúa.[19] Therefore, a key to revive a lost soul is communication and a willingness to share vulnerabilities with one another so that we are able to touch on the interconnectedness of change within our own self and others’.

Those experiencing Nepantla state are “Nepantleras.”[20] “Las Nepantleras are spiritual activists engaged in the struggle for social, economic, and political justice, while working on spiritual transformation of selfhoods.”[21] I call myself a queer Nepantlera where I witness myself going through pre- and post-suicidal thought processes. If the pre-suicidal stage witnessed my anger, where I used drawing to visually see the running thoughts in my mind, the bridge that connected the action towards it was quietness in my soul where I was struggling with facing different pressures that all came into place at the same time. The climax of the suicidal stage consists of moments when I stood up and confronted the line between life and death. “Craving changes, you yearn to open yourself and honor the space/time between transitions.”[22]The post-suicide witnessed another self of mine who was laying in the dark, jerking off to ease sleep after an unsuccessful attempt of reaching out for help from a suicide hotline. “In Nepantla you sense more keenly the overlap between the material and spiritual worlds; you’re in both places simultaneously— you glimpse el espiritu—see the body as inspirited.”[23] I split myself in between the realities to see realities. Then I write in this in-between space, craving changes. As Anzaldúa reminds me, “To write is to confront one’s demons, look them in the face and live to write about them. Fear acts like a magnet; it draws the demons out of the closet and into the ink in our pens.[24] Therefore, this piece is written to confront the demons in me that pushed me to think about committing suicide while I was in the bottom of my life. I write to challenge the demons of the society that push people like me—queer, fat, Asian, immigrant, people of color, students/teachers of color—in order to push back because I am strong enough to go through this shit and continue this life with others.

Craving Policy Change

This autohistoria, or “a personal essay that theorizes,” is a special piece to me.[25] This essay is spiritual, poetic, political, and dialogic. This essay delves deeper into the mourning, the fear, the tears, the pain, the loneliness, the strength of a Vietnamese queer immigrant in order to relate and provide rays of hope with/for the other queer Nepantleras in the dark (i.e. in suicidal process). I am not writing to propose a revolutionary policy for queer, Asian, immigrant, people of color; I am not a power holder in this society. However, as an empowered queer writer of color, I am exposing myself naked by weaving my lived experiences to “crave changes” for social transformation on this taboo topic.[26] I write this mental struggle out to answer the call “to look to sensitively explore the accounts of GB2SM [gay, bisexual, and two-spirit men] who experience current suicidality to generate unique insights and reveal therapeutic avenues.”[27] I therefore hope you find this piece useful to continue your life.

In terms of policy change, the state policy should do a better job when providing suicide hotlines for people like me. Am I too demanding to ask for that change to protect me and those who are in suicidal situations? I laid down there, calling in hopelessness. The person on the phone responding to me was not helpful at all; as if I were not important; as if I were not cared for; as if I were invisible. The waiting music, the beep sound ringing an alarming bell for you, policy makers. The service should not be created to serve political and economic purposes; rather, it should be initiated to save a human being who is desperate to continue to live. I hope my writing will ring a bell for you, policy makers who claim to advocate for us queer Nepantleras. I hope you will have some time to read this piece, to listen to us, to walk with us, to stand with us, to be present with us, to be able to split in between for us. Otherwise, when you really want to reach out to us, we will already be gone, far away, out of reach.

After all, I am glad I have courage to live; I am glad I could see the light in the darkest moments; I am glad I could see the splits in betweenness; I am glad I write; I am glad I live.

And, I hope you have courage to live as well.

Because this is how we continue to spread love and hope for others,

so that we can tell another story,

a story of what the suicide attempt feels like.

References:

[1] Gloria E. Anzaldúa and AnaLouise Keating, this bridge we call home: radical visions for transformation (New York: Routledge, 2002), 578.

[2] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 541.

[3] Ethan Trinh, “How hugging mom teaches me the meaning of love and perhaps beyond,” Journal of Faith, Education, and Community 2, no. 1 (2018): 1–14.

[4] C. Winter Han, Geisha of a Different Kind: Race and Sexuality in Gaysian America (New York: NYU Press, 2015).

[5] Trinh, “hugging mom.”

[6] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 549.

[7] Ethan Trinh (2020). “Still you resist: An Autohistoria-teoria of a Vietnamese queer teacher to meditate, teach, and love in the Coatlicue State,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (in press).

[8] Ethan Trinh, “From creative writing to a self’s liberation: A monologue of a struggling writer,” Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement 14, no. 1 (2019c): 1–10.

[9] Ethan Trinh and Luis Javier Pentón Herrera, “Writing as an art of rebellion: Scholars of color using literacy to find spaces of identity and belonging in academia,” in Amplified voices, intersecting identities: First-generation PhDs navigating institutional power, ed. Jay Sablan and Jane Van Galen (Brill: Sense Publisher, in press).

[10] Shinsuke Eguchi and Hannah Long, “Queer Relationality as Family: Yas Fats! Yas Femmes! Yas Asians!,” Journal Of Homosexuality 66, no. 11 (2019): 1589–1608.

[11] Judith Butler, Gender trouble : feminism and the subversion of identity (New York: Routledge, 2006).

[12] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, xxxiv.

[13] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 541.

[14] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 544.

[15] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 82.

[16] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 544.

[17] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 82.

[18] Trinh, “creative writing.”

[19] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 549.

[20] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 578.

[21] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 83.

[22] Anzaldúa & Keating, this bridge, 549.

[23] Anzaldúa & Keating, this bridge, 549.

[24] Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Toni Cade Bambara, This bridge called my back: writings by radical women of color (New York: Women of Color Press, 1983), 169.

[25] Anzaldúa and Keating, this bridge, 578.

[26] Anzaldúa & Keating, this bridge, 549.

[27] Olivier Ferlatte et al., “Using photovoice to understand suicidality among gay, bisexual, and two-spirit men,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 48, no. 5 (2019): 1540.