BY OFRA KLEIN

In 2000, during a presidential debate, then-candidate George W. Bush mispronounced the internet as “internets.” Four years later, he repeated this error in a debate with John Kerry (“I hear there’s rumors on the, uh, internets that we’re going to have a draft.”). This clearly was no mere mistake. And the internets responded—making this Bushism one of the first political internet memes.

Only a few years later, people became engaged on a wide scale with politics through memes. Memes were broadly used during the 2011 Occupy movement and the 2012 U.S. presidential election, which brought us classics such as Romney hates Big Bird, binders full of women and Amercia (there was a lot of Mitt Romney). While memes obviously made a point in mocking politicians, most were not born out of pure discontent or resentment. They were not primarily created to propagandize political views but were first and foremost funny.

Everything changed in the 2016 campaign, when internet memes were progressively professionalized and politicized. Even though memes were still primarily created by grassroot online communities, such as the Facebook groups Bernie Sanders’ Dank Meme Stash and God Emperor Trump, these images filled a valuable gap that was not covered by traditional campaign strategies. Memes were still funny, but the campaign period was characterized by a large number of nasty memes, aimed attacking opponents and spreading rumors. Images spread fabrications that Ted Cruz was the Zodiac killer, Hillary Clinton was on the verge of dying, and she was running a child sex ring in a pizza place.

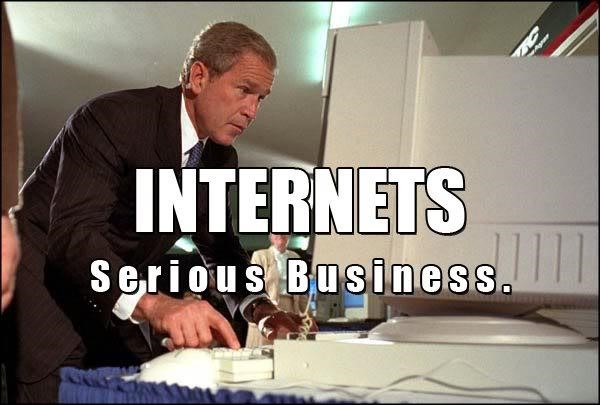

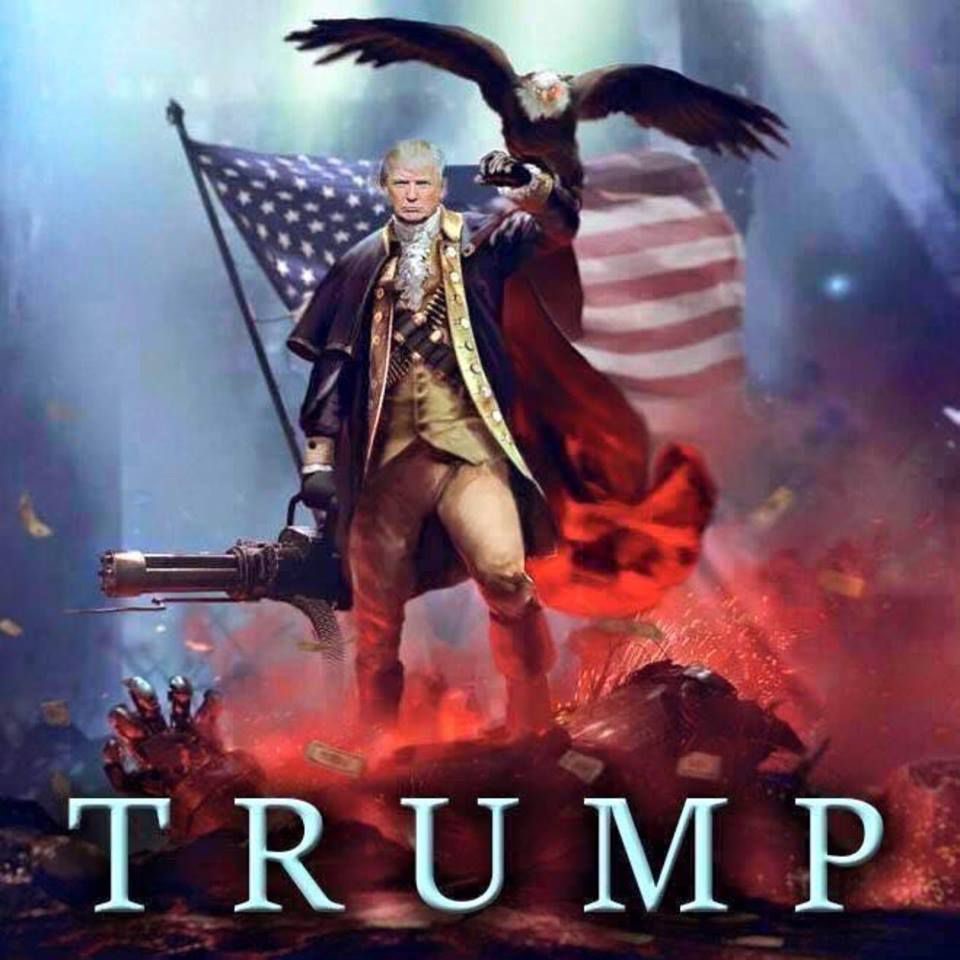

These memes, and the media attention surrounding them, generated ambiguity and doubt among voters. Network Propaganda, a book by researchers at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center describes how nearly half of Trump voters gave some credence to the Pizzagate rumor. Moreover, 12 percent of Obama supporters believed that Clinton had a serious illness. These findings suggest that memes can successfully influence people’s opinion on politicians. Memes can be used to undermine a politician’s reputation, but can also popularize them, as the memes portraying Trump in heroic ways do.

Memes are not a purely American phenomenon. In fact, memes are strongly bound to cultural traditions and contextual opportunities. In her excellent book Memes to Movements, An Xiao Mina shows how memes are used in very different ways by Chinese netizens. Limited technological and political opportunities make that memes in this environment have adapted: while straightforward activist messages are rarely effective, political criticism often relies on the use of coded verbal or visual language in order to avoid censorship (such as the Grass Mud Horse). These puns are hard to pick up on by people who are not part of the in-joke.

Cultural understanding is important for a meme’s success. The importance of cultural adaptation already lies in the terminology of the meme. Meme, a shortened version of the Greek word for imitation (mimeme) to rhyme with its genetic variant, refers to units of cultural transmission. Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who coined the term, argued that memes need to spread—and, if unsuccessful, adapt—from person to person in order to survive, like a virus. The same goes for internet memes, as internet culture scholar Henry Jenkins put it “if it doesn’t spread, it’s dead”. For memes to spread, they need to fit, and adapt to their cultural environment. Directly putting a meme from one context to another won’t work, as humor is strongly culturally determined, and references are often incomprehensible for outsiders.

The cultural meaning of a meme not only influences it success or failure, it also affects how harmful memes are perceived to be and in as much they are effective in mobilizing people. This became clear from the attempts of the American alt-right movement to transfer their controversial symbol, Pepe the Frog, into a transnational figure of the far-right. In contrast with their Chinese counterparts, American memes are often very explicit when expressing political discontent. Implicit memes that rely on dog-whistling strategies are, in this context, more often used to signal a message of group-belonging to like-minded others. Pepe the Frog, considered a symbol of hate, is one of these implicit indicators to signal belonging to the Alt-right movement. While hijacking a random frog (Pepe started out as a harmless comic) as a symbol did work for the American far-right, this was not the case in other countries. Half-successful attempts were made to adapt the meme as Pepe le Pen in France. However, the French connotation with frogs, which can be considered an insult to the French, makes the symbol useless for movements whose key feature is to express nationalist sentiment. Similarly, Pepe, as a symbol of antisemitism, does not appropriate well in countries that carry a painful mark of the Second World War

Despite their widespread attention and perceived success of memes in political campaigns. Marine le Pen, leader of the far-right French political party Rassemblement National (National Rally), even thanked her online army helping her gain second place in the 2017 presidential election. Memes are likely to gain more importance in a post-text future. Younger generations are shifting more and more to visual platforms such as Instagram and Snapchat. Images are therefore more likely shape their views on politics and politicians. While “cool politics”—such as Beto O’Rourke cleaning his teeth in a Story on Instagram, and congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez streaming herself while cooking mac and cheese—might engage youth in novel ways with politics, this can also limit the room for discussion, as every thought needs to fit into a tweet. When memes just form harmless jokes about mispronunciations this negative effect is limited, but when images start to effectively weaponize rumors and limit thoughts to soundbites, we need to reflect upon whether the evolution of political internet memes is going into the right direction.

Ofra Klein is a Ph.D. researcher at the European University Institute (Fiesole, Italy), where she works on online political mobilization and the radical right. Ofra previously worked as a research assistant at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and at Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society.

Source images: https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/internets; https://www.vox.com/culture/2018/8/8/17376824/trump-fan-art-maga-dinesh-dsouza-jon-mcnaughton

Edited by Michael Auslen